George Orwell’s 1984

George Orwell’s 1984 is often grouped with two other dystopian novels from the first part of the 20th century: We (Yevgeny Zamyatin, 1924) and Brave New World (Aldous Huxley, 1932). In Reading Global: In Big Brother’s Shadow we take Orwell’s warning on state totalitarianism as a start-point, for exploring core themes—surveillance, propaganda, censorship (and self-censorship), atomization, perpetual war and thought control—that remain politically relevant.

Orwell’s Oceania does not exist—that is, a super-state whose centralized economy is built around war, under strict Party control, with a leader (Big Brother/Stalin) whose authority rests in emotional appeal, by channeling hate against traitors (Goldstein/Trotsky) and external enemies (Eurasia or Eastasia). But elements of the world he imagines—continuous surveillance and the threat of denunciation by family members or workplace colleagues; the outlawing of positive, connective emotions (love, loyalty, mutuality) and the elevation of fear and hatred (“There will be no laughter, except the laugh of triumph over a defeated enemy” – O’Brien, Part Three, Section III); extreme polarization in political competition, and attempts to control memory/interpretation of the past—have continued to resonate.

Orwell’s vision has been a reference point for people living under repressive regimes (including, for example, Mao’s China, and Soviet Russia). 1984 has also sparked the imagination of novelists worldwide, including those who, like Orwell and his protagonist Winston Smith, value connection with the past (the paperweight, “… a little chunk of history that they’ve forgotten to alter” (145) the journal, the pleasure of reading (184-5) and lament its loss, especially when driven by an impulse to destroy such connections.

The book club is hosted at the Tempe Public Library, convened by Keith Brown. [email protected]. For the latest book club meeting register at: tempepubliclibrary.org and click Event Calendar.

Some start-up questions for discussion.

Why did O’Brien, and the Party, go to the trouble of writing Emmanuel Goldstein’s “Theory and Practice of Oligarchic Collectivism”—and making it available to Winston (and Julia)?

What should we make of the book as readers of 1984: and what should we make of Julia’s indifference to it, as well as other political topics that consume Winston?

Literary scholar Raymond Williams, in George Orwell (1971), is quite critical of Orwell’s character, Winston Smith. Williams writes he is “… not like a man at all—in consciousness, in relationships, in the capacity for love and protection and endurance and loyalty. He is the last of the cut-down figures—less experienced, less intelligent, less loyal, less courageous than his creator—through whom rejection and defeat can be mediated.” (82).

Do you find much to admire in Smith’s character?

Which term in Newspeak do you see as most disturbing, intriguing or best describes some aspect of contemporary U.S. life? (Candidates might include: Doublethink, Crimestop, Thinkcrime, Oldthink, Facecrime, Bellyfeel, Duckspeak.).

Contrasts

Orwell puts together the description of his neighbors’ family relations (especially, their party-loyal, hate-driven kids) with Smith’s recollections of his own mother and sister.

“Tragedy belonged in the ancient time, to a time when there was still privacy, love, and friendship, and when the members of a family stood by one another without needing to know the reason. His mother’s memory tore at his heart because she had died loving him, and he was too young and selfish to love her in return… (30).”

How important to the book are discussions of love, sex, reproduction and generation?

In Smith’s interrogation, O’Brien challenges some of the defining terms Smith has reflected on earlier: humanity, sanity, reality. “You would not make the act of submission which is the price of sanity. You preferred to be a lunatic, a minority of one. Only the disciplined mind can see reality, Winston. You believe that reality is something objective, external, existing in its own right….. reality is not external. Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else. Not in the individual mind, which can make mistakes and in any case soon perishes; only in the mind of the Party, which is collective and immortal” (249: Part Three, Section II).

Additional resources:

Raymond Williams devotes attention to Smith’s perception of, and lack of empathy toward, the “proles” – the 85% of Oceania’s population who are not party members, who are alternately presented as apathetic, or romanticized as revolutionaries against the system, if only they realized their state of servitude and ignorance. Williams sees in Orwell’s depiction of the proles traces of his own class background – it is “the world of working people as seen by the prep-school boy” (79) as well as signs that Smith has in fact internalized the Party’s propaganda. “…if the tyranny of 1984 ever finally comes, one of the major elements of the ideological preparation will have been just this way of seeing “the masses.”

Writing in 1971—informed by knowledge of successful resistance movements—Williams argues that Orwell’s projection has been proved false. “Under controls as pervasive and as cruel, many men and women have kept faith with each other, have kept their courage, and in several cases against heavy odds have risen to try to destroy the system or to change it. We can write Berlin, Budapest, Algiers, Aden, Watts, Prague in the margins of Orwell’s passivity.” (78)

“Doublethink is Stronger than Orwell Imagined” – George Packer, The Atlantic, 2019.

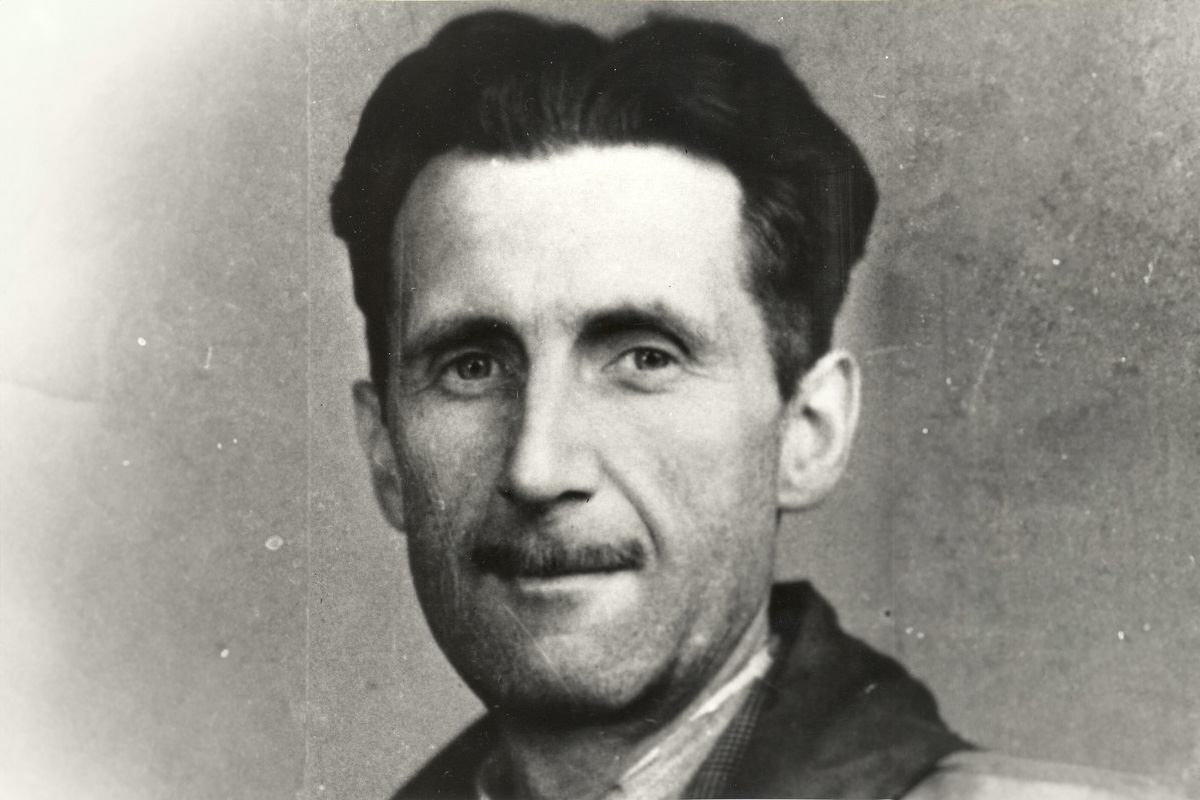

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitarianism, and support of democratic socialism.

Born in India, Blair was raised and educated in England from the age of one. After school he became an Imperial policeman in Burma, before returning to Suffolk, England, where he began his writing career as George Orwell—a name inspired by a favourite location, the River Orwell.

Orwell produced literary criticism, poetry, fiction, and polemical journalism. He is known for the allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945) and the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). His non-fiction works, including The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), documenting his experience of working-class life in the industrial north of England, and Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences soldiering for the Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), are as critically respected as his essays on politics, literature, language and culture.